GomBurZa and the Recoletos: Uncovering Historical Facts

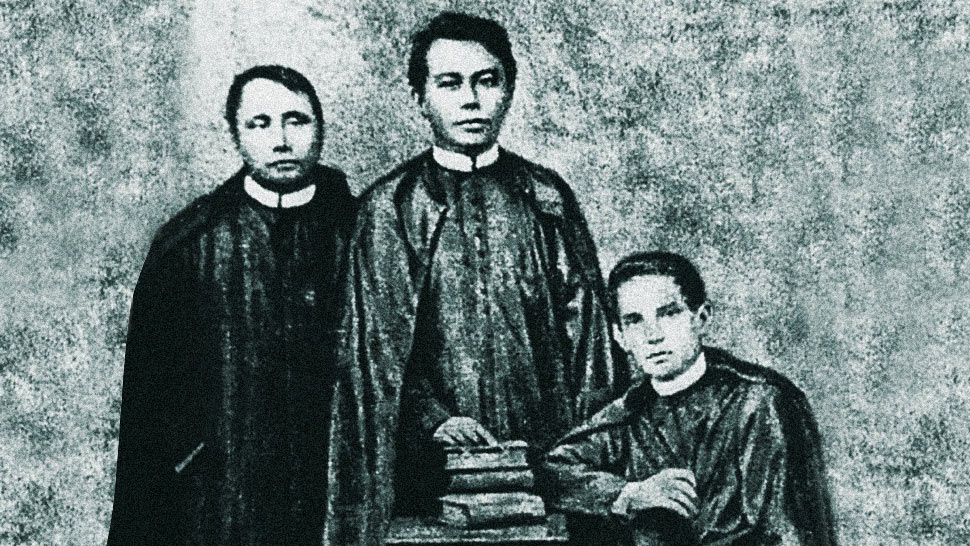

One hundred and fifty-two years ago, on February 17, 1872, three Filipino diocesan priests – Padre Mariano Gomes, Padre Jose Burgos, and Padre Jacinto Zamora – were publicly executed by strangulation, a method known as garrote vil, at Bagumbayan (now Rizal Park). They had been arrested on allegations of involvement in the failed January 20, 1872 Cavite Mutiny. Despite their pleas for a fair trial, their defense was never heard by the military tribunal. Instead, they were immediately imprisoned and sentenced to death by Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo.

According to Teodoro Agoncillo, a Filipino historian, the execution of the three priests marked a significant turning point in Filipino Nationalism. Their martyrdom served as a catalyst, igniting the flames of resistance and fueling the growing sentiment for independence. Indeed, this tragic event would later be recognized as a precursor to the Philippine Revolution of 1896, a pivotal moment in the nation’s quest for freedom and self-determination.

The GomBurZa tragedy was adapted into a compelling historico-biographical film, which emerged as one of the entries in the 49th Metro Manila Film Festival last year. This poignant cinematic portrayal garnered six awards, including the prestigious Best Cinematography accolade. Released nationwide in cinemas on December 25, 2023, the movie was a collaboration under Jesuit Communications’ production.

Congratulations on the commendable and largely faithful historical portrayal of the martyrdom of the three priests. However, the inclusion of artistic enhancements in the film occasionally veers into fictionalized and exaggerated scenes, straying from historical accuracy. These fictionalized elements, while potentially enhancing the narrative, should be recognized as departures from historical fact.

Four notable instances of this are evident:

Firstly, towards the conclusion of the movie, a scene depicts Jose Rizal at the age of 11 witnessing the martyrdom of the three priests. However, historical records indicate that Rizal was not present at Bagumbayan during this event; rather, he was in Calamba, Laguna. It was his elder brother Paciano who witnessed the death of their mentor, Padre Burgos.

Secondly, early in the film, a court litigation scene unfolds between Padre Pedro Peláez, representing the Filipino diocesan clergy, and the Recoleto friars regarding the transfer of Antipolo to the latter. While this adds dramatic tension, it deviates from historical accuracy. The portrayal of the Recoletos as eager to seize control of Antipolo does not align with historical records.

At this juncture, it is imperative to delve into the historical context surrounding the transfer of Antipolo to the Recoletos, a pivotal event that catalyzed the de-secularization of parishes in the Archdiocese of Manila, ultimately resulting in the transfer of diocesan parishes to the friars. This policy shift stemmed from Madrid’s apprehensions regarding the loyalty of the Filipino diocesan clergy. These doubts were precipitated by the Mexican Revolution of 1810, wherein Mexican diocesan priests spearheaded the quest for independence, culminating in the liberation of Mexico and subsequently, Latin America from Spanish rule in 1826.

The turning point arrived when Madrid made a significant decision regarding the Filipino diocesan clergy by permitting the return of the Jesuits to the Philippines, following their expulsion in 1768.

Ninety-one years later, on July 30, 1859, a Royal Decree issued by Queen Isabel II decreed the reinstatement of the Jesuits in the Philippines. Concurrently, the decree stipulated that the Recoletos were obliged to relinquish their missions in Mindanao to the Jesuits upon their vacancies. However, the Recoletos contested this mandate, expressing to the Spanish monarch the vastness of Mindanao and proposing a more equitable division of missions between them and the Jesuits. Regrettably, Madrid did not entertain their plea.

In response to the Recoletos’ petition, Queen Isabel II issued another Royal Decree on September 10, 1861. This decree, while compensating the Recoletos for the transfer of their Mindanao missions, mandated that they would immediately assume control of parishes in the Archdiocese of Manila as they became vacant. This development stirred apprehension among the Recoletos and cast them in an unfavorable light in the eyes of the Filipino diocesan clergy. Padre Peláez, serving as the vicar capitular of the archdiocese at the time, tirelessly worked towards the annulment of the 1861 decree.

In 1862, the church and shrine of Antipolo were left without a parish priest. Padre Peláez, seeking to uphold the interests of the diocesan clergy, asked the Recoleto prior provincial, Padre Juan Felix de la Encarnación, to abstain from submitting three names of Recoleto priests to Governor-General José Lemery, who would then select a parish priest for the shrine. Padre Juan Felix, displaying amicability towards Padre Peláez, acquiesced to the request. However, their efforts were in vain as the 1861 royal decree was swiftly implemented. The following year, 1863, Governor-General Rafael de Echagüe, Lemery’s successor, demandingly required the Recoleto provincial to present three Recoleto candidates for the parish of Antipolo. Reluctantly, Padre Juan Felix yielded to the governor-general’s directive.

During the Spanish colonial era, the Catholic Church in the Philippines operated under the “Patronato Real de las Indias,” a system in which the local church and its clergy fell under state supervision. This meant that the Spanish monarch and his representative in the islands, the governor-general, held authority over parochial assignments as dictated by the “Patronato Real.” In practice, bishops and religious superiors held little power within this system.

Towards the climax of the film, the friars convey their deep lamentation upon realizing that Governor-General Izquierdo had manipulated them as mere pawns in a scheme designed to undermine the Filipino diocesan clergy within the local church hierarchy. Later, as the Philippine Revolution unfolded, the intense anti-friar sentiment surged with unbridled fury, marking another sad chapter in Philippine Church History.

Thirdly, the failed mutiny in the Cavite arsenal stemmed from a misinterpretation of artillery explosions, mistakenly believed to be the signal of rebellion originating from Intramuros. In the movie portrayal, Francisco Zaldua, played by Ketchup Eusebio, informs one of his superiors that the mutineers erroneously heard explosions in Sampaloc, misinterpreting the celebration of its fiesta as a signal, thus prematurely initiating the mutiny. However, it should be noted that Sampaloc was not celebrating its fiesta at that time; rather, it was the Recoleto church in San Sebastian de Calumpang in Quiapo that was observing its patronal fiesta, marked by fireworks on January 20th. This particular date marked the fatal occurrence of the failed coup in the Cavite arsenal, a significant event chronicled in Philippine History textbooks

Finally, there was Padre Mariano Gomes de los Ángeles and the Recoletos. Padre Gomes, the eldest of the three priests, was 72 years old at the time of his execution. He had served as the parish priest of Bacoor, Cavite for an impressive 48 years. In 1847, he assumed the official role of Vicar Forane of the Cavite Province, appointed by the archbishop of Manila to oversee clerical discipline and diocesan property within his jurisdiction.

In the movie, Padre Mariano Gomes, portrayed by the veteran actor Dante Rivero, expressed his dismay, stating, “Hindi ako nirerespeto ng mga prayle…” (The friars do not respect me…). The friars present in the Cavite Province were the Augustinians, the Dominicans, and the Augustinian Recollects or Recoletos. Despite any tensions, it is worth noting that the Recoletos, who held haciendas and administered parishes in Cavite, generally maintained respectful relations with the Vicar Forane. Padre Gomes had a Recollect friar, Padre Juan Cruz Gómez, serving as his spiritual director and confessor. This same Recollect friar assisted Padre Gomes in drafting his last will and testament, bearing witness with his signature. In this document, Padre Gomes referred to his chaplain and confessor as “my friend,” entrusting his Recollect confessor to ensure the fulfillment of its terms after his execution.

The film “GomBurZa” has secured its place in Philippine Cinema by depicting a significant tragedy in Philippine history while also fostering the spirit of Filipino nationalism. However, due to constraints of screen time, the movie inevitably falls short in providing exhaustive historical details. A more attentive viewer may glean a clearer understanding of the historical context woven into the narrative. Nonetheless, those lacking a foundational knowledge of history may misinterpret the portrayal of the Recoletos as unjustly depriving Filipino clergy of their parishes—an assertion far from reality.

As for the Augustinian Recollects or Recoleto friars, they stand among the Spanish missionaries who dedicated themselves to the Christianization of the Philippines. The towns and parishes they established in Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao stand as silent witnesses to their unwavering commitment and sacrifices. Tears, sweat, and blood were shed in the arduous task of building a Christian community. To underscore this, during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, more than half of the Recollect missionaries perished before the age of forty-five, with only a handful reaching sixty. Many succumbed to shipwrecks, illnesses, and violent deaths.

While often overlooked in Philippine history, it is undeniable that not all Spanish friars resembled the Padre Dámaso depicted in Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere. The enduring Catholic faith in the Philippines bears witness to the sacrifices made by these missionaries in spreading the gospel to our ancestors. This faith persisted despite the immense territories they were tasked with, coupled with limited resources. Furthermore, through the Spanish friars, a fusion of Hispanic and native cultures manifested in the architectural splendor of colonial churches, the development of our languages, and the culinary heritage we cherish.

Indeed, it is undeniable that certain Spanish friars may have failed to live up to their calling. However, these shortcomings must not eclipse the unwavering dedication of the vast majority who diligently and silently worked in the Lord’s vineyard. As John Leddy Phelan astutely observes, “the spectacular vices of the minority ought not to obscure the less dramatic virtues of the majority.”

Rev. Fr. Emilio Edgardo A. Quilatan, OAR, professor of Church History, Recoletos School of Theology ([email protected])

Sources:

Romanillos, Prof. Emmanuel Luis A. “Fr. Pedro Peláez Unpublished Letters on the Secularization Controversy” in Quaerens Vol. 11, No. 2 (December, 2016), 5-68.

Phelan, John Leddy. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959.

Santiago, Luciano P.R. “The Last Will and Testament of Padre Mariano Gomes.” Philippine Studies vol. 30, no. 3 (1982), 395-407.